New York Times

By ANDREW JACOBS

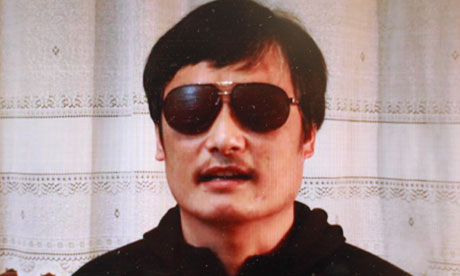

Did Chen Guangcheng, the blind self-taught lawyer who spent the past six days holed up in the American Embassy in Beijing, make China’s leaders blink? Or will American diplomats come to regret the agreement they helped negotiate on his behalf?

In the hours after he left the embassy on Wednesday with a deal that American officials said includes security guarantees for him and his family, there were competing narratives among Chinese rights advocates and elected officials in Washington over whether the arrangement, negotiated by Beijing and Washington, represented an unalloyed victory for Mr. Chen or an expedient and foolhardy concession to China’s authoritarian government.

And Mr. Chen himself seemed to be developing second thoughts about whether he could trust Chinese assurances that he and his family would remain safe inside China.

American diplomats and friends of Mr. Chen say that because he was not seeking political asylum in the United States but wanted to stay in China to continue his legal advocacy work, the agreement was the best denouement for a tense diplomatic drama that threatened to upstage a set of meetings this week, the United States-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, and bruise a relationship increasingly vital to both sides.

“I am pleased that we were able to facilitate Chen Guangcheng’s stay and departure from the U.S. embassy in a way that reflected his choices and our values,” Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said in a statement after speaking to Mr. Chen by phone as he was transported to a Beijing hospital for medical treatment.

But that optimism, shared by a number of human rights advocates both in China and abroad, began to fray later in the day after Mr. Chen began telling friends and foreign news outlets that he had changed his mind and was now seeking to leave China with his family.

Mr. Chen on Wednesday night told supporters that he had accepted the deal only after Chinese officials threatened to beat his wife to death. That account, while denied by American officials, could turn what had at first appeared to be a diplomatic triumph for the United States into a darker, more ambiguous tale.

Teng Biao, a lawyer who has provided legal help to Mr. Chen in the past, said Mr. Chen changed his mind after arriving at the hospital and talking to his wife and supporters. Speaking by phone from the hospital on Wednesday, Mr. Teng said that Mr. Chen grew especially concerned by the sight of so many plain-clothed police officers and by the realization that American officials had left the hospital for the evening. “The Chinese government has a habit of failing to keep their promises,” said Mr. Teng, who said he warned Mr. Chen of the potential risks if he stayed in China.

The British television program Channel 4 News also interviewed Mr. Chen, who reportedly said: “My biggest wish is to leave the country with my family and rest for a while. I haven’t had a rest day in seven years.”

Renee Xia, international director of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, said the Obama administration was naïve for accepting Beijing’s assurances that it would give Mr. Chen the freedom to continue his work — and his criticism of China’s failure to carry out long-stalled legal overhauls.

“The Chinese promise of Chen’s safety and freedom is unenforceable,” she said. “The government has no credibility — the record speaks volumes to the contrary — and I think this agreement will come back to haunt the Obama administration.”

Bob Fu, president of China Aid, an American Christian advocacy group in Texas, said he was worried that Mr. Chen had been pressured by both sides to agree to a deal before the start of the meetings, which begin Thursday. “I was a little surprised that he accepted the offer so quickly,” said Mr. Fu, an exiled Chinese dissident who wields considerable influence in Washington. “I don’t think he’s in a normal state of mind after seven years of trauma and these six roller-coaster days.”

But many human rights advocates said Beijing’s agreement to even discuss the terms of Mr. Chen’s release was significant, given that Communist Party leaders are loath to accede to pressure from foreign governments or individual dissidents. They noted that although Mr. Chen’s extralegal detention was carried out by provincial officials in Shandong, Politburo members were fully aware of his predicament and could have intervened.

They added that Mr. Chen’s case has been raised by numerous diplomats over the years, including Mrs. Clinton, and it was public security agents in Beijing who had abducted Mr. Chen and his family from the capital in 2006. After they were returned to Shandong more than 300 miles to away, Mr. Chen was tried and then sentenced to more than four years in prison on charges that Chinese legal scholars called spurious.

Jerome Cohen, an expert on Chinese law at New York University, acknowledged that the road ahead would be bumpy, but said the deal was significant because it freed Mr. Chen from the local authorities responsible for his continued persecution. Mr. Cohen said he thought it was unlikely that the Chinese side would renege on its word because the consequences to relations with the United States could be enormous.

“There still needs to be flesh put on these bare bones, but it could be new way forward for human rights lawyers,” said Mr. Cohen, a longtime champion of Mr. Chen who helped provide him with a custom-made laptop for the visually impaired that was later confiscated by public security agents. “The question is how much support will he get from the U.S. government and from the Chinese government, because they do have an interest in making this work.”

In the end, advocates say, Mr. Chen played his hand well by gaining entry to the American Embassy, but also by recording a video, posted on the Internet last week, that pleaded with the central government to intervene on his behalf. The video, in the form of an appeal to Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, blamed only local officials for his persecution and for wantonly trampling on Chinese law.

That gambit, analysts say, provided Beijing an opportunity to come off looking righteous.

Many rights campaigners on Wednesday said they were still amazed that the deal, as presented by American officials, provided so much of what Mr. Chen was seeking. The potential political costs to China’s top leaders, they said, were not insignificant.

“I’m astonished that Beijing bowed to the demands of Chen Guangcheng in such a public manner,” said Nicholas Bequelin, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch in Hong Kong. “The key question is whether the Chinese government can be trusted to keep its promise over the long term. But still, for now, they’re handing a significant victory to activists and to one of the most respected activists in China.”

No comments:

Post a Comment